While we’ve become quite use to ‘reimaginings’ in literature – especially in the classics, we very rarely get an honest to goodness reimagining mash-up, and even when we do, the mashing stays safely within one genre… It makes you wonder… can it be done any differently? Well, I guess Matt Ferraz had the same idea, because that’s exactly what he has accomplished with his work – Sherlock Holmes and the Glad Game. Below, I’m really happy to be able to share with you the book blurb and a guest post from Matt about his experiences writing Sherlock Holmes and the Glad Game.

The Blurb

British sleuth Sherlock Holmes can solve any mystery from a small clue. American traveler Pollyanna Whittier can only see the good side of every situation. The only thing they have in common is their friendship with Dr. John Watson. When Pollyanna shows up in London with a mystery for Holmes to solve, she decides to teach the detective the Glad Game: a way of remaining optimistic no matter what. A dangerous – and hilarious – clash of minds, where these two characters of classic literature need to learn how to work together in order to catch a dangerous criminal.

Guest Post by Matt Ferraz

Writing Sherlock Holmes and the Glad Game

The genesis of Sherlock Holmes and the Glad Game was a challenge I made to myself: pick two public domain characters that apparently have nothing to do with each other, and somehow make them work together. I’ve been a Sherlockian all my life, and wanted to write a book with the detective for some time. But who could I match him with? Other writers already crossed Holmes Jack the Ripper, Mr Hyde, Captain Nemo and so many others. What could I bring to the table that was new and fresh?

I was at a bookshop in my home town when I saw brand new editions of Pollyanna and Pollyanna Grows Up, by Eleanor H. Porter. Those were books I had never read, but knew the basic premise: a girl who always sees the bright side of everything no matter what. I had seen the 1920 movie with Mary Pickford, one of my favourite actresses, but remembered little of it. So I bought copies of those two books, and while reading them, a novel started to form in my mind.

No one had ever had the idea of putting Holmes and Pollyanna Whittier in the same story. After all, they’re so different! But my mind was made up: I was going to write a book where Pollyanna comes to London and assists Holmes and Watson in an investigation.

The one month first draft

People didn’t believe I could pull it off. In fact, my fiancée thought it was a crazy idea to begin with, but decided to give me the benefit of doubt. I wrote the first draft of this book in a month – faster than I had ever worked before! For that whole month, I was completely immersed in the story, having re-watched several Holmes movies for inspiration and re-reading big sections of Porter’s books.

My idea wasn’t simply to have Pollyanna ringing at 221b Baker Street offering a case for the detective to solve. I wanted to fit her in the Holmes canon as organically as possible. My book starts with Pollyanna becoming a good friend of Dr. and Mrs. Watson while Holmes was considered to be dead after facing Professor Moriarty.

Bringing the two together

Pollyanna is in London to see a special doctor due to an injury she suffered in her childhood – which is shown in the first Porter book. She eventually returns to America, but shows up in London two years later, when Holmes is already back from the dead, with a brand new husband and a lot of trouble on her back.

The best part of writing this story were the comedic possibilities in the interaction between these characters. I tried to avoid making Pollyanna too annoying and naive – she’s actually pretty smart and kicks a few butts. It was also nice to create a more humane Holmes, different from the stubborn and arrogant versions we’ve seen in movie and TV in the past few years. It’s a little, quirky and funny book I’m very proud of.

Signing off, Matt.

If you want to learn more, you can contact Matt on Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter: @Matt_Ferraz

“In a novel, place is inseparable from character and events. Indeed it can become an effective character in itself, a protagonist, soaked in mood. My novel A Burning in the Darkness begins in the prayer room of one of the world’s biggest airports. There is a tiny confessional box and in its anonymous darkness a voice confesses a murder to Father Michael Kieh, but a young boy has witnessed the killer go into the confessional. Michael becomes the main suspect in the murder investigation because of a group of pitiless antagonists, but he doesn’t betray the identity of the young boy nor break the Seal of Confession.

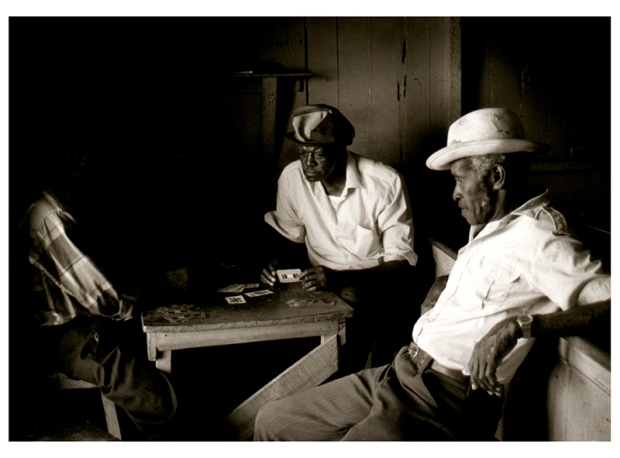

“In a novel, place is inseparable from character and events. Indeed it can become an effective character in itself, a protagonist, soaked in mood. My novel A Burning in the Darkness begins in the prayer room of one of the world’s biggest airports. There is a tiny confessional box and in its anonymous darkness a voice confesses a murder to Father Michael Kieh, but a young boy has witnessed the killer go into the confessional. Michael becomes the main suspect in the murder investigation because of a group of pitiless antagonists, but he doesn’t betray the identity of the young boy nor break the Seal of Confession. I was struck by the way they explore the intertwined relationship between character and environment. In technical terms the portraits are taken with a wide angle lens so that you see both the person and the surroundings. I was drawn to the looming Soufrière Hills volcano at the centre of the island and it becomes the backdrop to many of the photographs. However in July 1995, the volcano erupted and destroyed most of the main habitable areas, including the principle town, the airport and docking facilities. Two thirds of the population was forced to leave, mainly to the UK.

I was struck by the way they explore the intertwined relationship between character and environment. In technical terms the portraits are taken with a wide angle lens so that you see both the person and the surroundings. I was drawn to the looming Soufrière Hills volcano at the centre of the island and it becomes the backdrop to many of the photographs. However in July 1995, the volcano erupted and destroyed most of the main habitable areas, including the principle town, the airport and docking facilities. Two thirds of the population was forced to leave, mainly to the UK.

The quality of the relationship between the subject and the artist is crucial. The degree of imaginative sympathy for the subject is something that sets a good work of art a part from others. The ultimate skill is not in mastering the camera or a fancy ability with words; it is getting the subjects to reveal themselves – even if the subject is entirely your invention.”

The quality of the relationship between the subject and the artist is crucial. The degree of imaginative sympathy for the subject is something that sets a good work of art a part from others. The ultimate skill is not in mastering the camera or a fancy ability with words; it is getting the subjects to reveal themselves – even if the subject is entirely your invention.”